The Air War

Flak, Fighters, and the Sky Between

The cold was the first thing I noticed that morning, up where the air thins out. The engines droned on long enough to disappear into the background, until there was a sharp pop—then another. I leaned toward the window and saw black puffs hanging in the sky, neat and round, right where we had just been. A moment later, silver shapes slid in from the side, moving fast and deliberate, close enough to make you forget everything else.

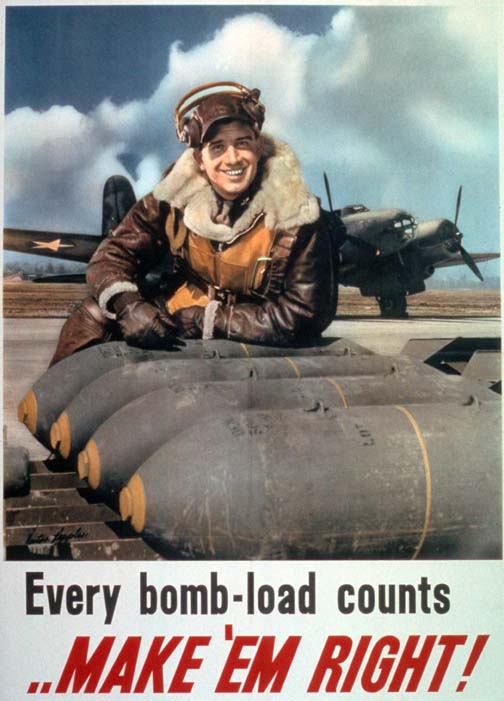

The air war was fought far from the ground, in an environment that punished mistakes immediately. Crews faced multiple dangers at once—mechanical failure, weather, enemy fire, and the physical strain of operating at altitude for long periods.

Combat rarely arrived all at once. It built gradually, often beginning with anti-aircraft fire and followed by enemy fighters probing formations for weakness. Each threat required a different response, and crews were trained to react without hesitation.

Anti-Aircraft Fire

Flak was a constant presence over enemy territory. Bursting shells filled the sky with fragments designed to tear through aircraft and crews alike. Even near misses could damage engines, controls, or structural components.

Crews learned to recognize flak patterns and adjust formation and altitude when possible. Still, much of surviving flak came down to discipline—holding position, maintaining speed, and trusting the aircraft to absorb punishment.

Enemy Fighters

Fighter attacks were faster and more personal. Enemy aircraft approached from blind spots, attacked in coordinated passes, and withdrew just as quickly. Gunners scanned constantly, tracking movement against the sky and clouds.

Fighter encounters demanded split-second coordination between pilots, gunners, and formation leaders. One aircraft breaking formation could endanger many others. Staying together was often the difference between survival and loss.

Weather and Altitude

Weather was an adversary that could not be fought. Clouds, icing, turbulence, and poor visibility complicated navigation and formation flying. At altitude, extreme cold reduced dexterity and strained both men and machines.

Oxygen systems, heated clothing, and constant monitoring became routine. Even so, crews operated at the edge of human endurance, where small failures could escalate quickly.

Command and Pressure

Orders came from above, but their consequences were felt in the aircraft. Mission parameters—altitude, route, timing—were set on the ground, sometimes with limited information. Crews learned to execute plans precisely, even when conditions changed unexpectedly.

Pressure existed at every level: to complete objectives, to protect other aircraft, and to return with as many crews intact as possible.

A War of Attrition

The air war was not decided in a single engagement. It unfolded through repeated missions, gradual losses, and accumulated experience. Crews adapted, tactics evolved, and aircraft designs improved in response to what was encountered in the sky.

Survival depended on learning quickly and applying those lessons immediately. The margin for error was narrow, and the cost of failure was high.

Continue Through WWII

-

Reconnaissance

-

Winning WWII

-

Wartime Culture